Minnesota House of Representatives; Georgia House of Representatives; Marianne Ayala/Insider

- The past election cycle saw a record surge in AAPI voter turnout, helping Democrats in swing states.

- But an increase in civic engagement may not turn into more Asian Americans running for office.

- To address that, AAPI leaders are aiming to create pipelines for young people to elected office.

- Visit Insider's homepage for more stories.

Fue Lee and Jay Xiong are part of a cohort of young Minnesota state representatives who have been steadily growing the Hmong community's political power in the state.

Lee was elected in 2016 when he was 24, and is serving his third term in the state legislature. He was the first person of color and of Asian descent to represent Minneapolis, a major metropolitan area home to one of the largest Hmong populations in the country.

"For me that's where it all started, where we started understanding that all politics is local – where our elected officials, they're not really reaching out to communities, especially those like the Hmong community where we make up a decent population in the area that I live in," Lee told Insider.

Xiong, who is serving his second term representing Minnesota's St. Paul area, was elected in 2018 when he was 36, and says his interest in politics was first piqued during a college course on Asian and human rights issues.

Though Xiong was involved in grassroots organizing long before running for office, he only did so because he got "really sick and tired of no representation," he told Insider.

Hmong Americans like Lee and Xiong currently occupy a record-setting six of the state legislature's 201 seats, but they've been building their political power for nearly two decades - starting when Mee Moua became the first Hmong American elected to the Minnesota state legislature, as well as any US state legislature, in 2002.

Across the country, there's been a growing number of Asian Americans casting ballots, running for office, and working in political campaigns.

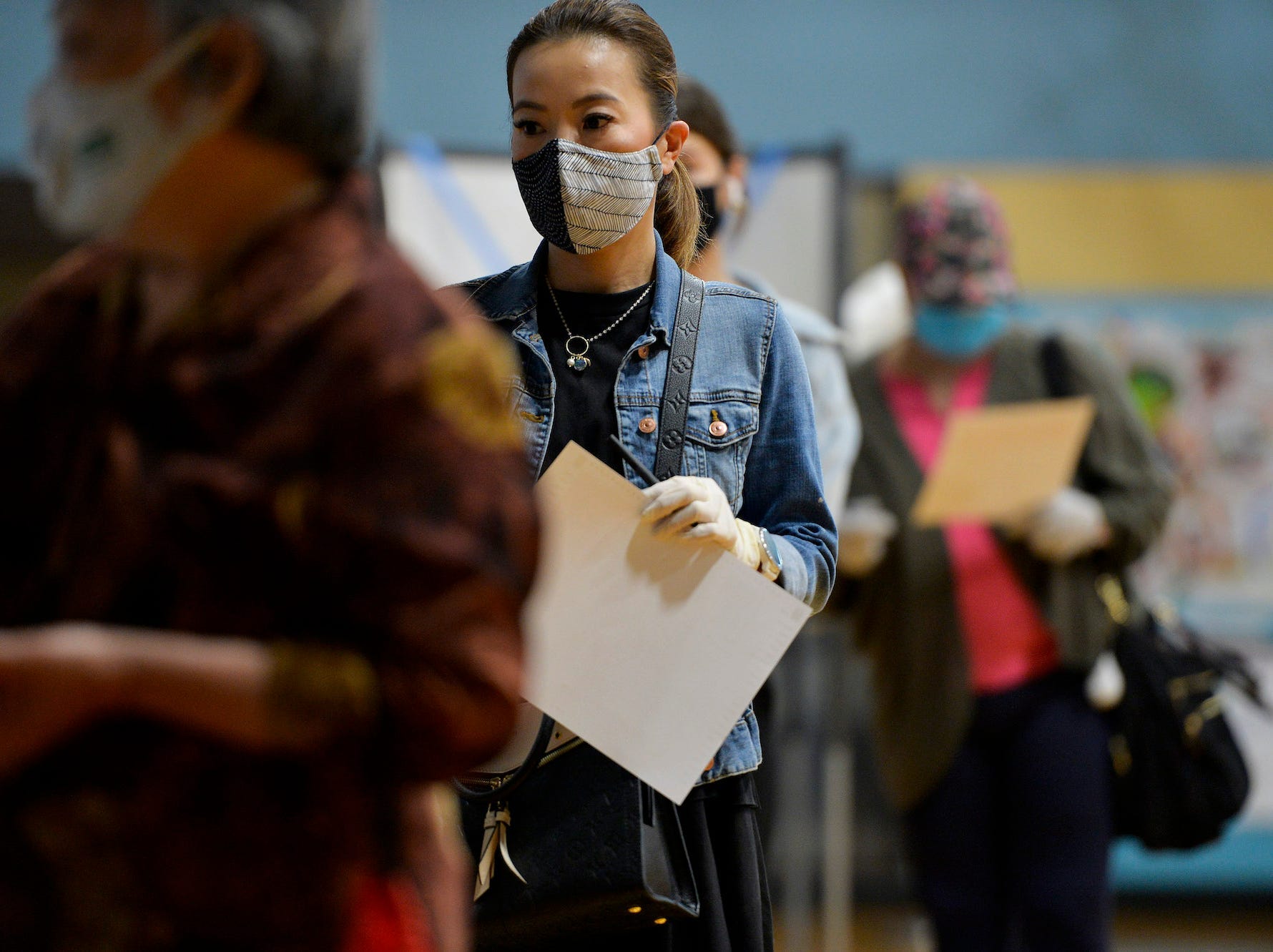

According to Christine Chen, executive director of the nonpartisan civic organization Asian Pacific Islander American Vote (APIAVote), 2020 saw a historic surge in AAPI voter turnout. It increased by 10 percentage points - the highest of any racial or ethnic group.

As the Asian American voting body grows and changes however, AAPI leaders say there still isn't enough attention being paid to the community from major political parties up and down the ticket.

In the meantime, community-based groups and nonprofits have been picking up the slack - working to build pipelines of talent to set the stage for the next generation of Asian American political leaders.

AAPI voters are 'leaning in' because of the pandemic and rise in anti-Asian violence

Xinhua/Wang Ying via Getty Images

Noting the rise in anti-Asian violence and hate crimes over the past year, including the March shooting in Atlanta that killed six women of Asian descent, Chen told Insider there's been a lot of pain in the Asian American community - long before lawmakers and the larger public began taking note of violence and harassment directed at AAPIs.

Chen says APIAVote, which focuses on increasing Asian American civic participation, was surprised by the "tremendous numbers" of AAPI voters in the 2020 presidential election, whereas prior to November's election, young AAPI voters had actually started to "reverse course."

"They always were typically the lowest segment of our population in terms of being registered and turning out, but they actually had increased their involvement in the 2018 midterms," she said.

A combination of factors contributed to the higher voter turnout, including a once-in-two-decade event where a presidential primary and Census occurred at the same time, Chen noted.

Many community-based organizations were able to combine their messages when reaching out to AAPI voters: conducting Census outreach and welfare checks, doing pandemic-related education, and helping manage the rise of anti-Asian racism and violence.

The pandemic also increased AAPI voter engagement because they could clearly "connect the dots between why their vote matters and how that's related to issues that they care about," Chen said.

At the same time, more Asian Americans began paying attention to the news for pandemic updates, and started recognizing how politics impacts their daily lives, she said.

Asian American leaders say there's not enough investment from major political parties

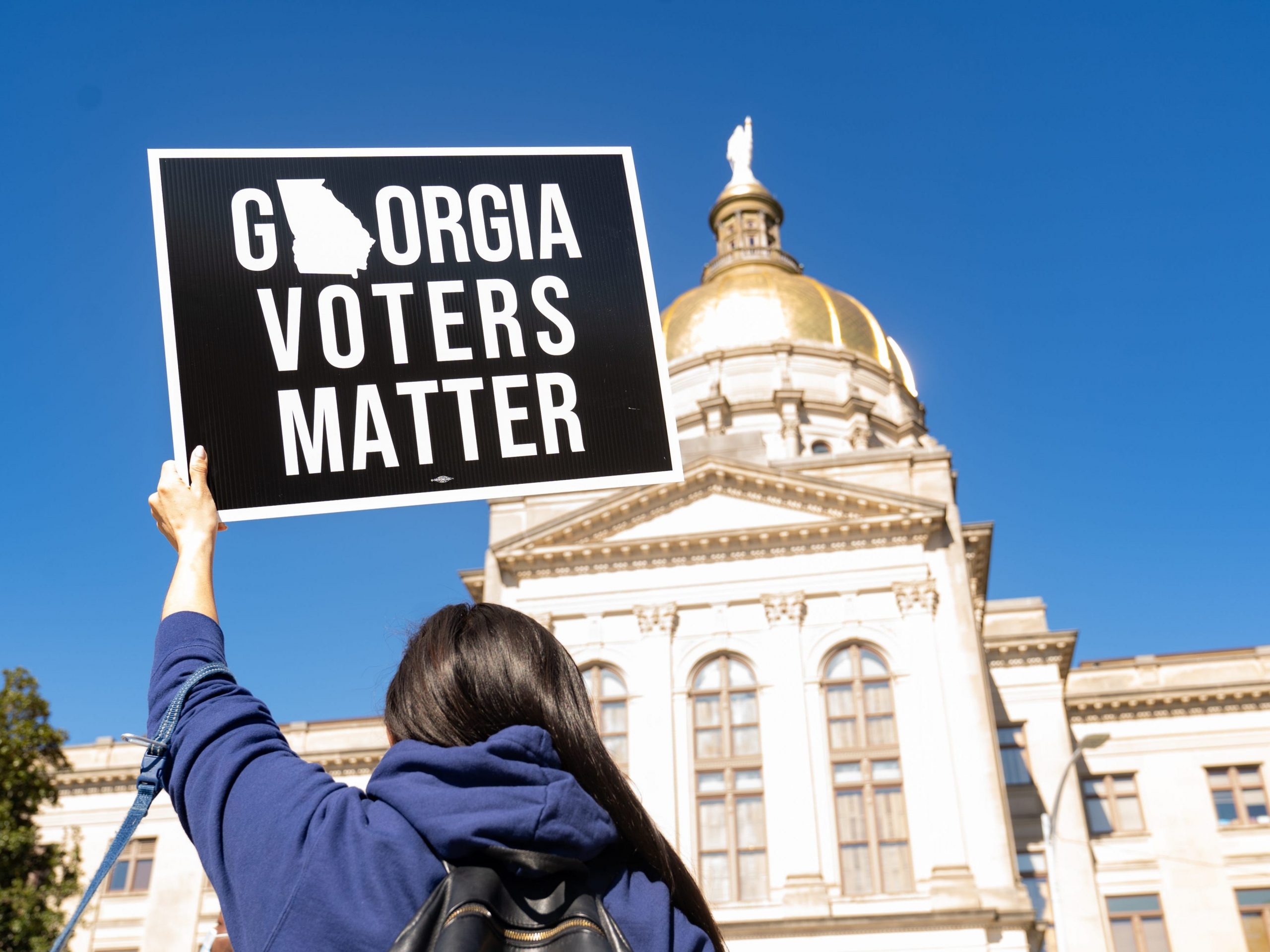

Megan Varner/Getty Images

Still, leaders in the Asian American community have been sounding the alarm for many election cycles that Democrats and Republicans are not paying enough attention to the growing AAPI electorate.

Asian Americans make up 7% of the US population, but are the fastest growing minority group.

And there's clear evidence AAPI voters are becoming engaged and voting in higher numbers than ever, especially in decisive elections like the Georgia Senate runoffs and other critical swing states, according to TargetSmart, a provider of Democratic election data.

"I'm always still saying that the parties can not take any of the communities for granted," Chen said. "Once you're elected, it's also about engaging them and asking their opinion as you make decisions along the way on different public policy issues."

Sam Park, a Korean American serving his second term as Georgia state representative, calls Democrats and Republicans' lack of investment the biggest roadblock to increasing AAPI political engagement, and said it "perpetuates this cycle of non-involvement and remaining on the sidelines."

Indeed, when Democrats ran a coordinated campaign in Georgia in 2020 - tailored to Asian American voters - AAPI voter turnout jumped 62,000 votes compared to four years before, TargetSmart figures show. Biden won the state by less than 13,000 votes.

"Seeing it very quickly change, in which we're seeing intentional efforts to reach out to this very diverse community in their own languages in a multilingual, culturally competent manner - clearly their results speak for themselves," Park told Insider.

How political action can be sustained in the Asian American community

JOSEPH PREZIOSO/AFP via Getty Images

To ensure AAPI voter turnout is not an anomaly, Park says Democrats and Republicans need to continue engaging with Asian Americans, so "they understand that they have political power and that they use it appropriately, to vote in their best interest and hopefully the best interests of this country."

Chen also worries that some might consider the record AAPI turnout to be "just a blip." But the rise in anti-Asian violence is not going away, she says, so "a lot of those concerns that motivated our community to turn out to vote are still there."

"We know from experience, and also from working with our allies in the Arab American, Muslim American, South American communities that hate waves have a long tail," Tiffany Chang, director of community engagement at the nonprofit Asian Americans Advancing Justice (AAJC), told Insider. "We have long lasting ripples and we are nowhere near done."

Now, Chen's group APIAVote is preparing to educate Asian American voters on local elections in 2021, including the high-profile mayoral primary in New York City on June 22, where former Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang, a Taiwanese American, is currently one of the frontrunners.

But Chen acknowledges the group has more work to do in turning motivation around stopping anti-Asian hate into political action - that includes teaching the AAPI community how to reach out to elected officials, asking school boards to incorporate Asian American history in their curriculums, and asking city councils to dedicate more resources to mental health and English language services.

Still, there are signs that AAPI political action will be sustained, especially from wealthy and high-profile members of the Asian American community.

Executives from Zoom, YouTube, and DoorDash recently donated $10 million to AAPI community groups, and other prominent Asian American business leaders raised more than $1 billion through The Asian American Federation, which counts actor Daniel Dae Kim and CNN host Lisa Ling among its advisors.

Because of that increase in giving, Chen says nonprofits serving AAPIs are better equipped to grow along with the community. She also cites private foundations like the Coulter Foundation, which donated $45 million to funding AAPI political engagement from 2014 to 2018.

At the individual level, AAJC's Chang says the group is encouraging Asian Americans to channel the energy they put into stopping anti-Asian violence to learn about AAPI history and support organizations that provide direct services to their local Asian American communities.

"This hate is not the beginning of the work, it is an extension of it," she said. "We recognize that we have to change the culture and create one in which we're not perpetuating an environment where xenophobia and racism can persist. And that is something that every person can do."

Creating a pipeline to elected office for the next generation of Asian American leaders

Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

Though there was a 15% increase in Asian Americans running for state legislatures last year, according to organization AAPI Data, only 17 of the nation's 535 members of Congress are Asian American.

Despite the growth in AAPIs running for office, Chen says one of the ongoing challenges for the Asian American community is encouraging more to make that leap. To start, getting Asian Americans involved in civic engagement programs like phone banking, door knocking, and talking to voters ultimately makes them feel more comfortable running for office, she said.

"The more we get our community to become voters and also not just be passive voters," Chen said, "We're going to see a lot more people also run for office."

Still, some Asian American elected officials are celebrating the changes they've seen firsthand.

"One of the things I'm most proud of over the past five years in which I've been in office is to see the number of Asian American elected officials go from one, which is how many there were when I was first elected, to five," Georgia representative Park said.

And while there was a lot of attention paid to the lack of AAPI representation in President Biden's cabinet, Chen says there are thousands of other jobs in politics Asian Americans should be candidates for.

"When we get someone in the door, and the experience, then that actually creates a pipeline for them to actually go for the next round, to be appointed for a more of a high-level position," she said.

In Minnesota, Lee and Xiong said building their pipeline of Hmong leaders took time, and included participating in programs run by the Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus. Lee was an organizer with Xiong before running for office, and says the Hmong community has been purposeful about selecting and training its future representatives.

"We're not necessarily waiting for our turn when we actually think we can have a fighting chance to run for office and win," he said. "And so now it is up to us here in Minnesota to be intentional about training the next wave of political organizers and candidates."

For Xiong, the end goal is that running for office changes from "a far-fetched idea" to an expectation within Asian American communities. "If it can happen to you in Minnesota," he said. "It can happen anywhere in this country."

The Karen community, an ethnic group from Myanmar, might be next to test out the Hmong community's blueprint for political action, Xiong says. With over 17,000 members in the state, one of the nation's largest, Xiong said the Karen community's political struggles in Minnesota mirror those the Hmong community faced early on.

But before phone banking, and even before taking part in programs that prepare them for elected office, Park says Asian Americans need to recognize that government works for them.

Prior to the pandemic, he would bring groups of Asian Americans to the Georgia state legislature to say, "Welcome to the people's house. This is your house."

"I think we'll continue to see greater Asian American representation and civic engagement from Asian American voters, because seeing themselves reflected in government and these elected positions really does make a difference," he said. "I think the message that it sends to Asian American voters, immigrants, first time voters, is that this is their government as well."